Nerd alert: This is the first article of a two-part series. It is a bit more heavy on the statistical vocabulary than other posts on this blog. You have been warned.

The downfall of the SPD

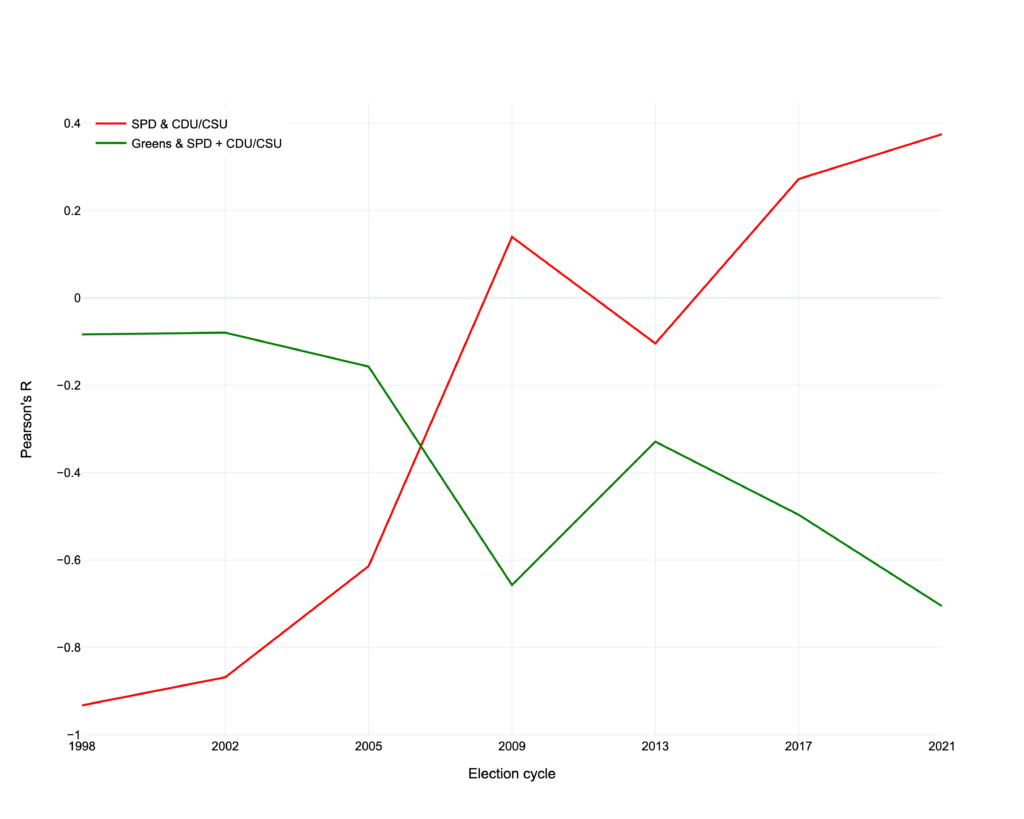

The chart above explains one of the most important developments in German politics over the past 27 years. Read on because it’s going to take me two blog posts to explain why.

The chart shows how the Vorcast Polling Average of the SPD, CDU/CSU and the Greens are correlated (you can go here to find out more about the average and German polls). The X axis is the election cycle, denoted by the year the election took place in. The Y axis is a value called Pearson’s R. Pearson’s R goes from -1 to 1 and denotes whether two things are positively or negatively correlated. For the context of German politics, this means: the higher up a number on the Y axis is, the more those parties’ numbers move in tandem. The lower it gets, the more they move in the opposite direction.

For this first part, we’re going to focus on the red line. Which, as you will notice, went up with almost every election cycle.

Two sides of the same coin

Germany used to work similarly to a two-party system. There was the SPD (the Social Democrats), the center left and the CDU/CSU (the Christian democrats), the center right. For the first 56 years of Western and then unified Germany, these two parties basically mirrored themselves in popularity.

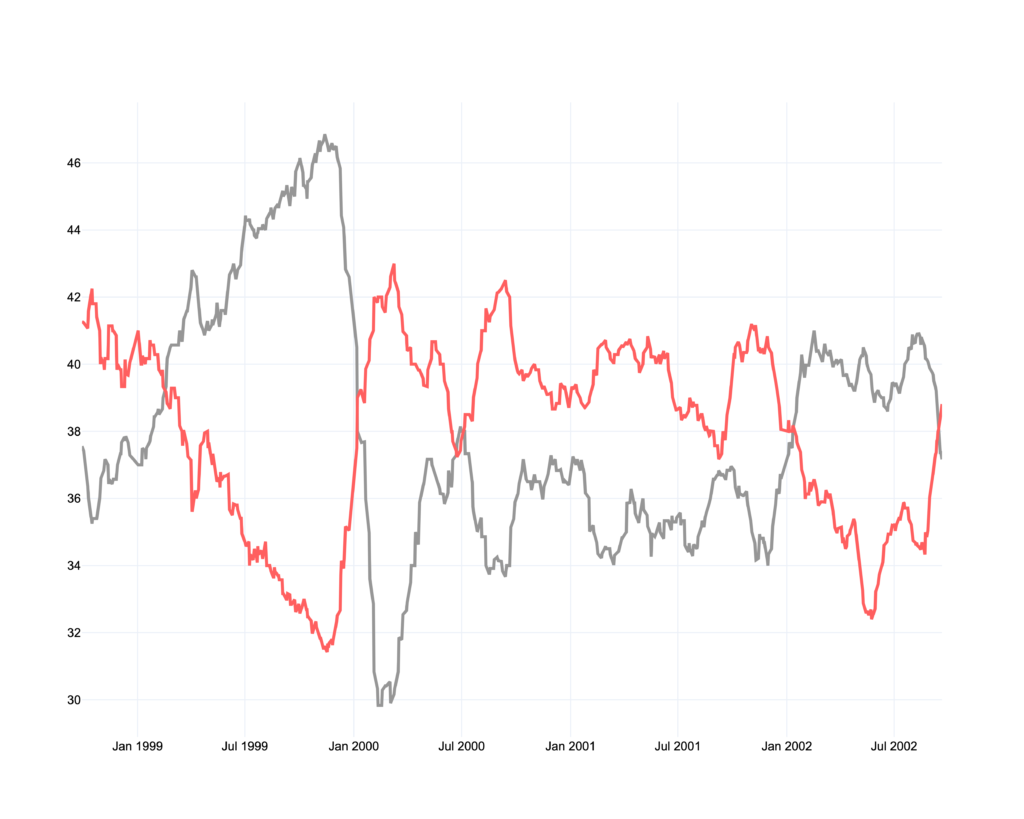

If we look at the 2002 election cycle, this relationship becomes immediately apparent. The polling averages almost perfectly mirror each other, meaning where one party loses, the other gains. This was the way German politics worked for 56 years. Then, in 2005, something weird happened: both parties began governing together. This is referred to as a grand coalition.

In 56 years of modern German democracy, either party ruled Germany by themselves or with the FDP (a conserative, libertarian party) as a junior party (the CDU/CSU for 36, the SPD for 20 years). In only three of these 56 years, Germany was ruled by an arrangement which would become the main form of coalition during 12 of the 16 years of Angela Merkel’s chancellorship: the grand coalition. This moniker was given because it is particularly “big” in terms of the share of votes represented by these two parties.

Not so grand for the SPD

This grand coalition fundamentally altered the relationship between the two parties. Remember that red line from the chart at the top (the one that basically only went upwards)? It represents the relationship between the SPD and the CDU/CSU. With (almost) every election cycle their relationship became less negatively correlated but under the first grand coalition from 2005 to 2009, it becomes positive for the first time.

For the four years from 2009 to 2013, the CDU/CSU’s junior partner was the FDP. This is the only period in the last 23 years where the relationship between Germany’s two major political rivals did not become more positively correlated. They re-entered a grand coalition in 2013 and their fates became more intertwined again.

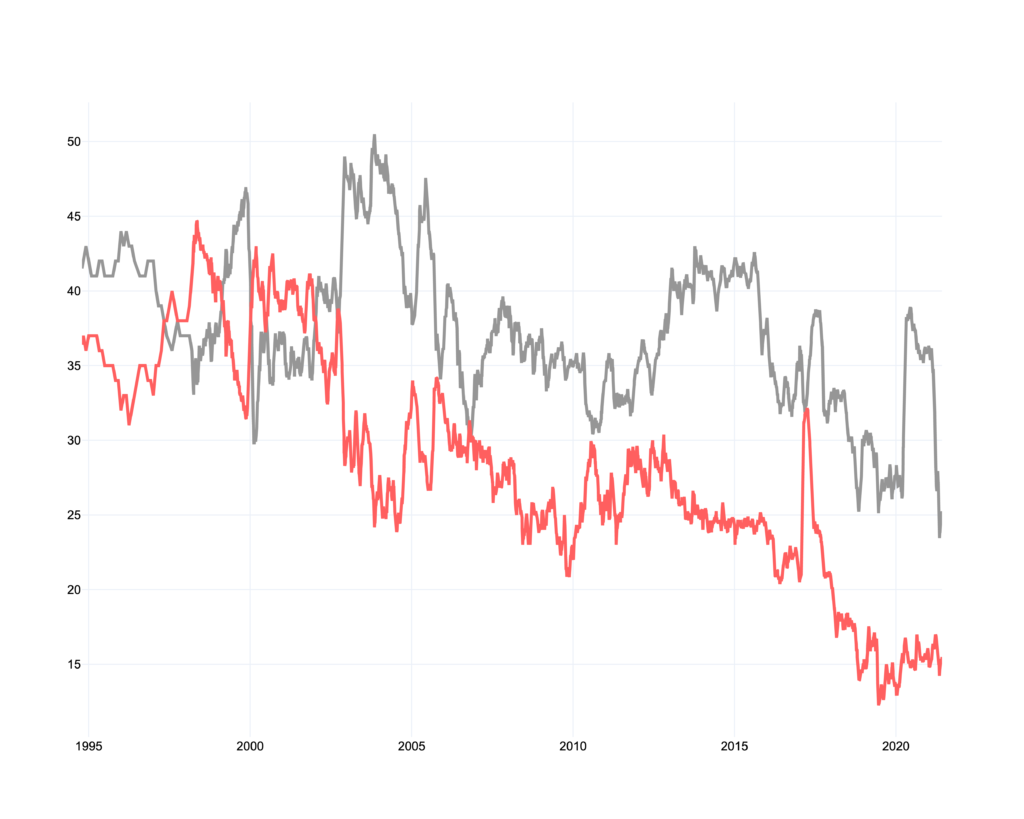

Except, as you can see above, the Christian Democrats remained the most popular and influential German political party and the SPD continually declined. So what changed?

Compounded problems for the Social Democrats

If the parties move so much in tandem, how come the SPD is doing so much worse than the CDU/CSU? It would be too simplistic to simply point to the grand coalition as the sole reason for the SPD’s continuing decline, but the evidence is definitely there to at least attribute a large part of the reason to it. The SPD went from an almost perfect negative correlation during the election cycle of 1998 to a solidly positive one today.

If you read the chart at the top carefully, you will see that SPD went from almost -1 to about 0.4, meaning that the parties do not move completely in tandem. There are many other reasons why the Social Democrats are doing so poorly, many are known, others are more subject to interpretation. To list just a few:

- neverending internal squabbles

- the rise of the hard-left party Die Linke

- controversial, if economically successful, reforms to the welfare state by the last SPD-led government under chancellor Gerhard Schröder (1998-2005)

Many other European countries have seen the decline of center left parties, but usually the center right does not fare much better. Not so in Germany though. The CDU/CSU has had ups and downs, but they remain the most powerful and popular political party today.

The SPD and the CDU/CSU have been perceived as more and more similar over the past 27 years, much to the detriment of the former. In a way, this takeaway really isn’t all that surprising or shocking. If two parties govern together for 12 out of the last 16 years, why wouldn’t voters have a somewhat similar opinion about them? Yet, this insight isn’t something that is generally accepted in the parties themselves or in the media. The fact of the matter is: it’s one variable in a complicated equation, but it is one that I would argue is basically undeniable at this point.

In the next post, we’ll look at another overlooked fact in German political history. It’s generally accepted that the Greens today are the main alternative to the CDU/CSU. What is less understood, is that this development already started back in 2010.

First of all: Great website and awesome modeling! I always asked myself why we never look at polling averages in Germany and why we focus so much on single polls.

I take, however, issue with this: “It’s generally accepted that the Greens today are the main alternative to the CDU/CSU.”

It certainly seems that way based on current polls. But I don’t think this is the case. At least not yet. The Greens have more seats than the SPD in only three state parliaments: BW, Bayern and Saxony. In Saxony they are so weak that they pose no threat to either CDU or AfD. The SPD continues to have significantly more seats than the Greens when we look at the aggregate of seats in all state parliaments. Plus, the Greens are the smallest party in the Bundestag as of now (something that will change come September). And in terms of party membership, CDU and SPD are well ahead of all other parties.

In order to become a main alternative, the Greens would need to prove to be the second largest party in multiple federal elections. I have, however, doubts about this given their significant regional weaknesses. And their previous fluctuations in support.

Thank you for the praise and feedback.

You make a really good point about the differences between the state and the federal level. German state electorates can look a lot different from the national environment. I probably should have pointed out more that I am focussing exclusively on the national level. Another thing to keep in mind though, is that even on the state level we might see some pretty big changes soon in terms of the Greens overtaking the SPD (for example in Berlin).

Also, please check out the second part of this post once it is up. I will explain more about how the Greens took over the mantle of the main opposition party.