Sometimes the obvious take is the right take, even though it’s boring. Germans don’t like change. The Christian Democrats have been in charge for the last 16 years and they will almost certainly be in charge after September’s election as well. Get used to saying chancellor Armin Laschet.

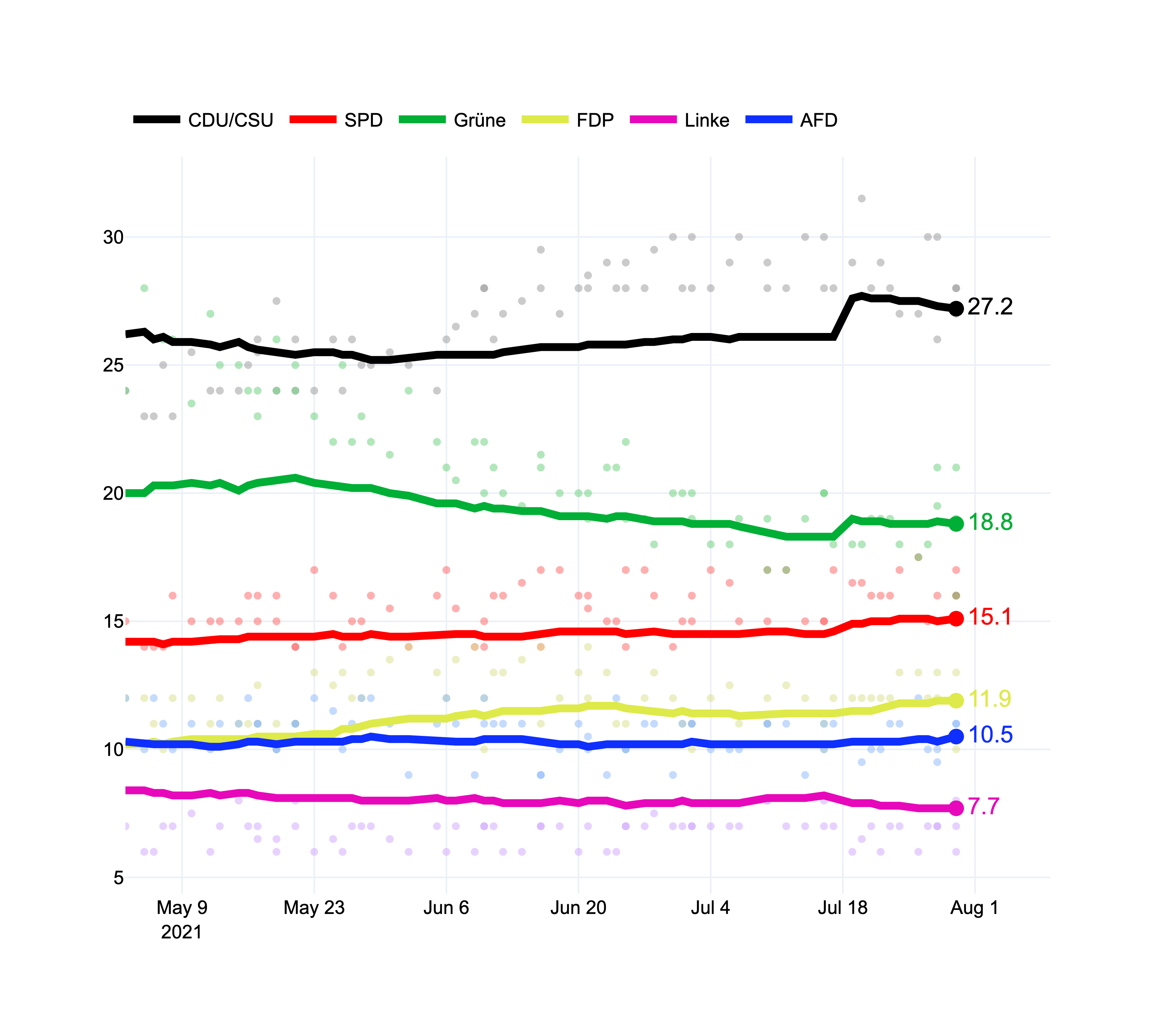

My model has predicted the CDU/CSU to be the most popular party throughout the entire election cycle of 2021. Contrary to the polls, my model never showed the Greens overtaking them. The chance of any of that happening (or of the SPD making a comeback) is extremely unlikely and has been since at least March 2021 (when I launched this blog).

Read on for some historical context and why major shifts in the electorate are unlikely at this point. Then, I’ll explain what the Vorcast model’s most likely election results are and what the resulting coalition might look like…

Same same, but different also same

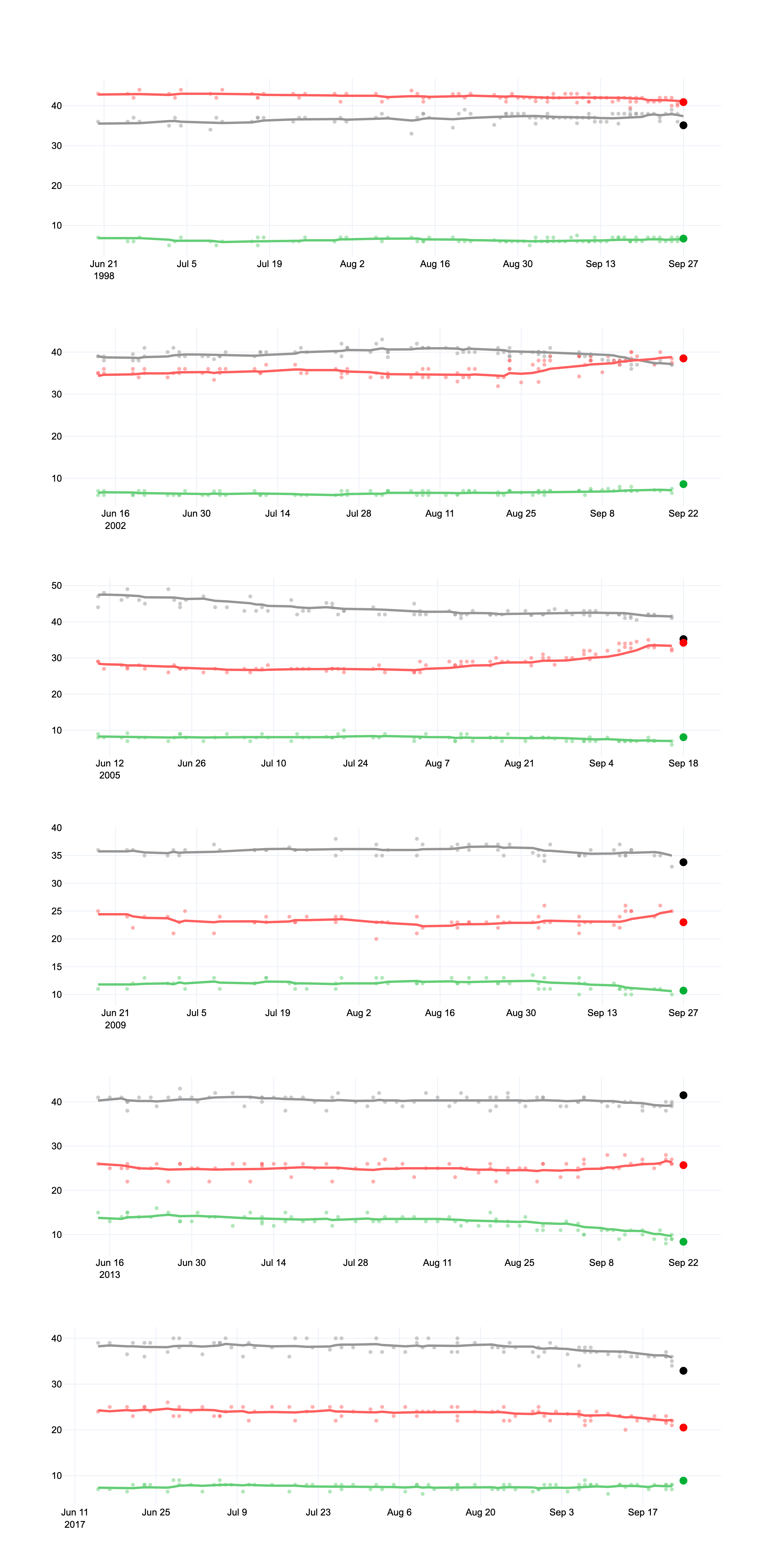

The chart below shows the polling averages for the CDU/CSU, SPD, and the Greens in the final 100 days of the last 6 elections. With the exception of 2002, the three parties always finished in the same order in terms of popularity (though the Greens were not always the third-most popular party overall). At this point in the race, the parties had introduced their candidates and their platforms, had run their campaigns and tried to get their messages across. But none of this matters too much to voters. The German population made up their mind for the most part at this point of the race.

The one exception is 2002 when there was a “Jahrhundterflut” (flood of the century). Germany went through a flooding disaster in the summer of 2021 that was significantly worse than the one in 2002. Nonetheless, recent polling suggests that this year’s flood of the century doesn’t seem to have shaken things up at all in terms of the election. I think the main reason is that none of the three main candidates for chancellor currently hold that office. Though Armin Laschet is the Minister-President of North Rhine-Westphalia, one of the states most affected by the disaster, neither he nor his two rivals, Anna-Lena Baerbock for the Greens and Olaf Scholz for the SPD, seem to have garnered or lost support because of the disaster.

So the past has shown us that things don’t change much in terms of what party comes out on top. But this year’s election outcome depends on extremely small percentage points. Now that we’ve reviewed the past, let’s use my model’s forecast to try to see what the future will hold.

We’re going to Jamaica

If you’re not familiar with German politics, “Jamaica” refers to the black, green and yellow party colors of a coalition government between the CDU/CSU, Greens and FDP. And somewhere along the way, we decided to call this coalition “Jamaica” — like the country’s flag. More on this in a second.

Even if I might sound like a broken record, I think my take from back in March on the election outcome is still my current one. It will be a very close election, the outcome of which will mostly depend on the strength of the CDU/CSU and the Greens.

The current forecast shows which coalitions could be possible after the election. The only one that would be realistic and cross the 50% threshold would be a “Jamaica” coalition. The second-most likely outcome (which is well within the margin of error) would be a two-party coalition between the Christian Democrats and the Greens. To me, this coalition is less likely because the CDU/CSU is a risk-averse party and would rather govern with a solid majority than with a razor-thin one supported only by the Greens.

Coalitions aren’t a straightforward numbers game, though. In 2017, Jamaica was also the first option on the table, but the negotiations imploded when the FDP walked away. There are many more variables than just the vote share involved in coalition negotiations. To name just a few: party platform compatibility, pressure from the party bases, pressure from the party elites, ministries up for grabs, how well the people involved get along, egos, etc.

To be clear: I stand by my prediction that a Jamaica coalition is the most likely (closely followed by a two-party coalition by the Christain Democrats and the Greens). I just want to acknowledge the uncertainty that comes along with complex coalition negotiations. My model tries to predict the voting share of each of the major parties and I base my predictions for what the next German government will look like solely on that. To my knowledge, there is no model that uses a politician’s egos as an input. If there is, I’d love to see it.